In honour of LGBT+ History Month 2024

Content warning: names and portraits of queer people who were taken too soon—but includes no details of their passing.

I performed a new spoken word piece, ‘Family Tree,’ as part of the Spit it Out takeover event at the Push the Boat Out Festival in November 2023.

This poem was inspired by a prompt from Devotion Workshop to write out a queer ancestry tree, to imagine and claim its myriad real, fictional, or conceptual ancestors. ‘Family Tree’ names Sappho, Audre Lorde, Phantom of the Opera, dungarees, meadows, scrapbooks, fan fiction, pen pals, among many others.

It also lists a number of people taken too soon, like Declan Flynn. Matthew Shepard. Marsha P. Johnson. Roger Casement. Kitty Genovese. (Content warning: these links lead to Wikipedia articles where their lives & deaths are detailed.)

Sharing these names felt important in describing a lineage. Moving through the world as a queer person—and moreover, a visibly queer person—my visibility and my work are forever and inextricably indebted to them.

But it also feels delicate: acknowledging strangers as important to me can make them into symbols, and erase them of individuality and nuance. It’s why their stories are important.

Let me tell you a little bit about them—and what I think about when I list their names.

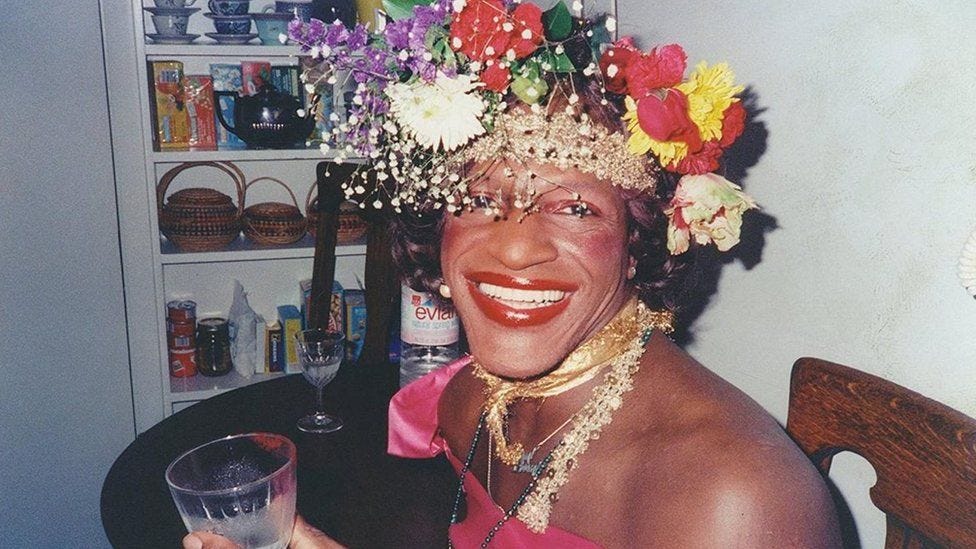

Marsha Pay-It-No-Mind Johnson was a sex worker, rebelling against dirty cops and homophobic culture norms for the sake of queers and queens living on the streets of New York. She was a major AIDS activist for ACT UP. And she was fabulous.

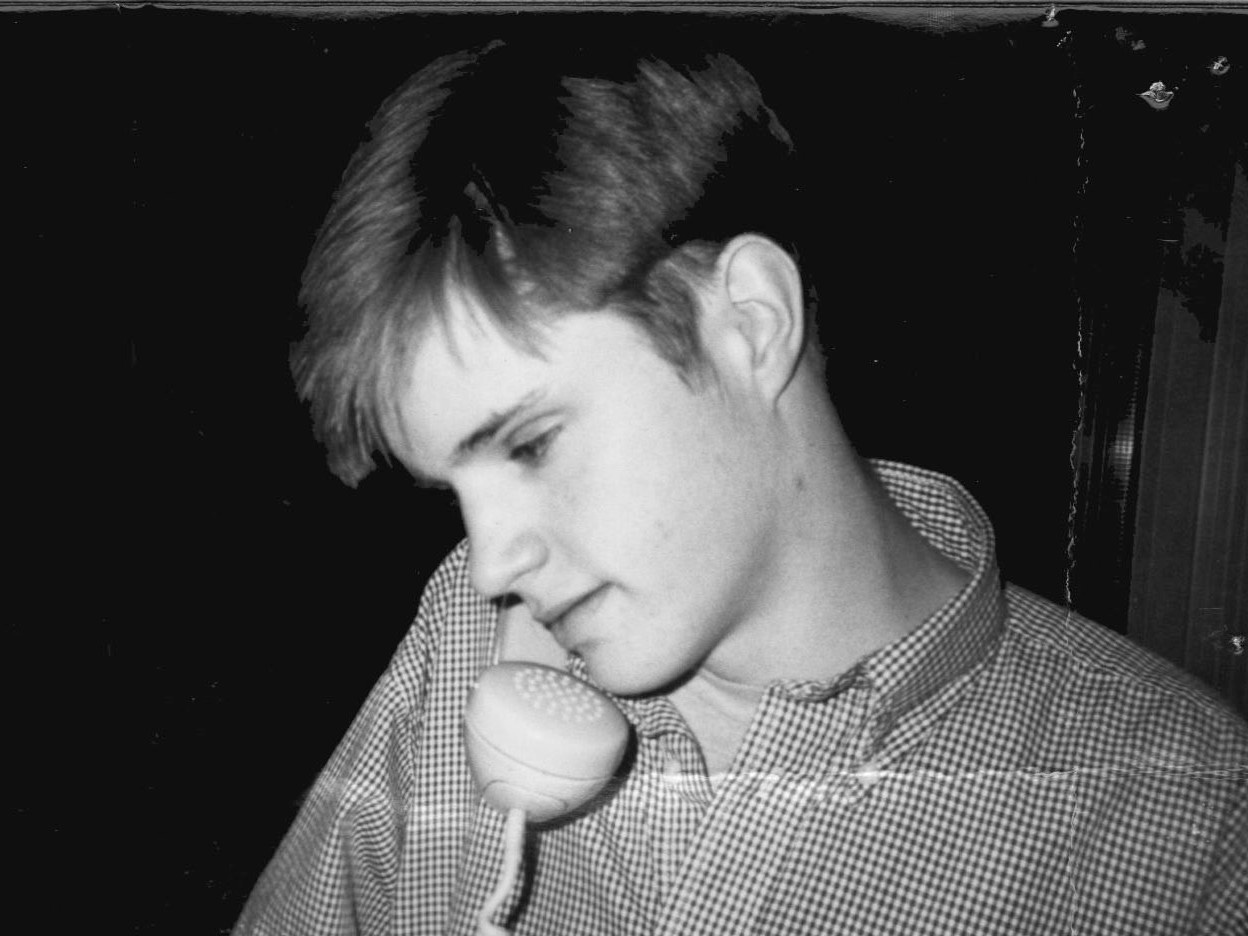

Declan Flynn was a volunteer at a gay community centre in Dublin city centre, whose last kind touch was a kiss on the cheek.

Matthew Shepard was a political science student and student rep for the Wyoming Environmental Council.

Kitty Genovese was a bartender in New York, saving up to open her own Italian restaurant.

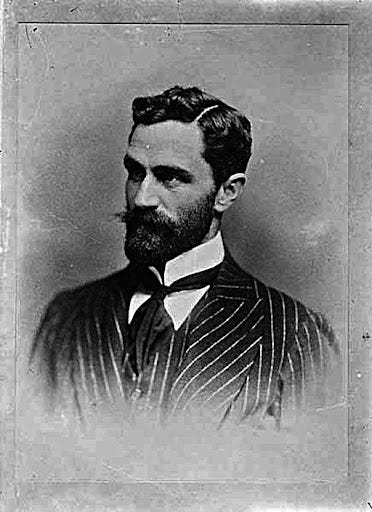

Roger Casement was a diplomat in the British Foreign Office. After witnessing the horrors of colonialism in the Congo, he turned against British imperialism and became a key part of the Republican movement. When Casement was brought to trial for treason, Arthur Conan Doyle authored a petition to the Prime Minister seeking clemency.

There’s another reason that sharing these names in the poem feels important, a reason that’s stranger and harder to accept: I never knew about these stories until I came out. Until that point, they were completely invisible to me.

I might have read Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen in my undergraduate classes, but they were just war poets. (And: they were also both queer men who had a deeply romantic relationship.)

I might have heard about Eva Gore-Booth in history class, but she was just the lesser-known sister of Constance Markiewicz. (And: she was a queer labour activist, and editor of Urania, the radical subscription journal published from 1916-1940, spreading news about feminist movements worldwide, lesbian women in history, and editorials challenging society’s gender norms.)

There was a whole new history hidden by, and behind, the one I’d been taught. There was a whole new culture hidden by, and behind, the one I’d been raised in. There was a whole new community I had barely begun to access, or feel belonging to.

This is the double-edged sword of what ‘coming out’ means: you see how much the tools of oppression have built and warped your reality and your sense of self, you see them clearly for the first time, you see how they work, how they have always worked, you see the structures that they built are transparent, you see their scaffolding and duct tape, you see the smoke and mirrors, and suddenly, suddenly, you see that many of your neighbours, coworkers, managers, family, friends - don’t.

When I talk about this with my partner, they echo the feeling, and summarise it exactly: a feeling of your inner world expanding, while your external world is shrinking.

As a poet, then, describing my queer ancestry, I think firstly of all these names—these people who have been taken too soon—and momentarily it can feel destabilising to think about how I could be one of them. The risk of being seen, weighed up against the need to be witnessed.

But really, it’s not a competition at all—I’ll take the risk every time. Every time. Partly out of my own stubbornness, I admit, but mostly because that defiance is the beautiful inheritance of queer ancestry.

(I think of Oscar Wilde quipping, from his deathbed, ‘My wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. One or other of us has got to go.’)

Defiance is the bedrock of being proud when others demand that you feel shame. And queer poetics, as Devotion Workshop has deftly taught me, lets you take hold of the tools of oppression, systemic injustice, trauma, grief, and defiantly use them as tools for creativity and self-determination.

I am indebted to these queer ancestors for the same reason as my genetic ones—without them, I couldn’t exist.